What do Houston, Miami and Phoenix have in common? Besides being among the biggest and fastest-growing cities in the U.S., they are also facing some of the biggest risks from climate change.

- Phoenix already suffers from a heat-wave season that grows longer and more intense every year. The 2018 National Climate Assessment1 states that the city’s temperature may break 100 degrees on as many as 150 days per year by the end of the century.

- Houston suffered tremendous losses from Hurricane Harvey in 2017, and each hurricane season brings renewed potential for flooding and other storm-related disasters.

- Miami’s sea level has risen by 3.5 inches since 1992 and is projected to rise another 14 to 26 inches by 2060.2 This is an existential threat for a city that already experiences regular high-tide flooding, even on clear, sunny days.

These cities and many others are on the front lines of the consequences of climate change, and they are taking the dangers they face more seriously. They are starting to build out the infrastructure needed to combat the impacts of a warming planet—and they are issuing substantial municipal debt to pay for those projects.

We are highly focused on the climate-related risks associated with any municipal bond investment we make. We are pleased to see that cities and states—as well as the agencies who assess their creditworthiness—are also focused on these risks. The market as a whole is pushing for more rigorous climate risk disclosure, and issuers are funding a wide variety of high-impact projects aimed at climate mitigation and adaptation.

“WE ARE TAKING THESE RISKS VERY SERIOUSLY”

All municipal bonds are issued, at least in theory, to produce a public benefit, so the asset class offers some inherent appeal to impact-minded investors. Climate change is a different animal, however—it is just as much about tangible credit risk as it is about positive impact.

Given the harrowing projections about global warming in the coming decades, many investors have pushed for years for credit-rating agencies to take climate risk more seriously. It appears that the agencies are indeed sharpening their focus. Moody’s, S&P and Fitch have all issued warnings to state and local governments in the past few years that climate-risk exposure may affect their credit ratings in the future. Moody’s in particular has been active in bolstering its ability to assess climate risk, purchasing Vigeo Eiris (a leading ESG research firm) in April 2019, and then in July acquiring a controlling interest in Four Twenty Seven, a leader in data and analysis related to physical climate risks. Four Twenty Seven’s database quantifies climate risks in detail for more than 2,000 listed companies and—germane to our discussion of the municipal market—more than 3,000 U.S. counties. (The headline of this section is a quote from Myriam Durand, global head of assessments at Moody’s.)

The increased attention from ratings agencies coincides with increased focus on the problem by many cities and states. At the beginning of 2019, Moody’s surveyed the 50 U.S. cities with the largest amount of municipal debt outstanding; of the 28 that responded, more than 80% expect to have a climate risk action plan in place by the end of this year, and more than half plan to issue debt to fund climate initiatives. The respondents have collectively proposed or launched 240 climate resilience projects with a combined cost of $47 billion, $21 billion of which will be funded by the cities themselves (as opposed to federal or state funding).

The overriding goal of these projects is to stave off the consequences of climate change, but issuers also know that viable climate plans will be a growing factor in their credit ratings going forward. There are few cases of actual credit downgrades so far, but we have seen a few examples that suggest a precedent for the future—for example, Cape Town, South Africa’s downgrade in 2017 due to drought, and the downgrade of Trinity Public Utilities District in California earlier this year due to elevated risk from wildfires. The fact that agencies are positioning to quantify climate risks more effectively may spur additional issuance going forward, and we also believe that issuers will feel the need to provide better risk disclosure. Miami’s Forever Bond is a good example: approved by voters in 2017, the measure will devote nearly $200 million to projects that mitigate the impact of current and future sea-level rise. The program is based on a thoughtful, long-term approach in which six initial $10-million demonstration projects will inform how the city allocates capital to climate adaptation in the future. This is supported by the fact that Miami-Dade County has also bolstered efforts to provide straightforward and transparent discussion about the risks facing Miami in the coming decades.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT

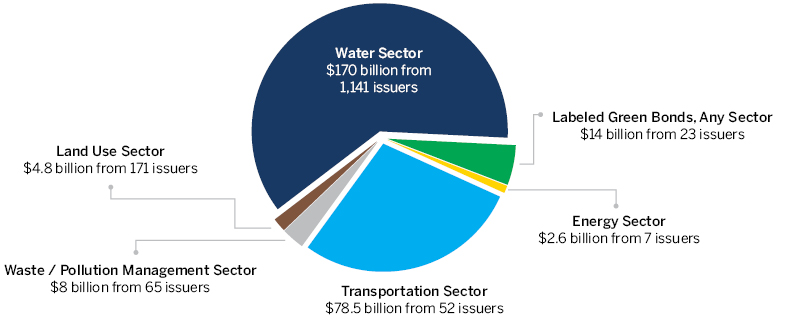

In our view, the municipal market offers a robust pipeline of climate-related investments, aimed at mitigating climate change by accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy, and adapting to the consequences of climate change through bolstering existing infrastructure (see chart below). Labeled green bonds offer one avenue of exposure, but we look well beyond the green label to a more expansive universe of bonds across many sectors. We believe that investing in this space requires a real commitment to in-house ESG research, so we can truly evaluate the sustainability merits of issuers and ensure that bond proceeds are being used to generate real impact. This research has become an essential component of our fixed income investment process.

Transportation: The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) reports that more than 40% of buses and 25% of rail assets are in marginal or poor condition in the U.S., and that there is a backlog of $86 billion in deferred maintenance and replacement needs. We look to invest in transit systems that are improving accessibility and quality, with a particular focus on light rail systems and/or electric vehicle bus fleets. We have also invested in measures that support development and improvement of sidewalks and bicycle lanes in high-density environments. Overall, these measures take cars off the road and consequently reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

THE CLIMATE-ALIGNED MUNICIPAL BOND UNIVERSE

Research from the Climate Bonds Initiative in 2018 identified a $264 billion climate-aligned municipal bond universe. In addition to a healthy pool of labeled green bonds, this universe includes a wide range of other bonds issued by water, transportation, energy and other agencies with a “pure-play” focus on climate-related issues and challenges.

Climate-aligned "pure-play" U.S. municipal bonds: A $264 billion universe

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative

For instance, we frequently invest in bonds issued by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which finance a sprawling system that offers public transportation alternatives to over 15 million people. Every year, travel via MTA (vs. by car) avoids 19 million metric tons of greenhouse gases; the entity emits only 2 million through its operations. This net result makes the MTA one of the single largest contributors to greenhouse gas avoidance in the U.S. Spurred in part by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the MTA has also implemented measures to increase its resiliency to catastrophic events, such as elevating critical infrastructure, retrofitting older assets and improving emergency response.

Energy: Municipal issuers—electric utilities, to be precise—have been key supporters of the growth of renewable energy in the U.S., leading up to 2018 when renewable sources accounted for about 17% of all U.S.-generated electricity. In recent years, issuance in this sector has broadened to some extent, to encompass traditional deployment of renewable generation, programs to encourage greater demand-side energy efficiency, and initiatives to harden existing infrastructure to withstand rising temperatures, prevent wildfires and generally adapt to the changing climate.

A recent investment of ours in this sector was a labeled Green Bond from the Berkshire Wind Power Cooperative Corp. Berkshire operates the second largest wind farm in Massachusetts, and the green bond is central to the issuer’s goal to expand current wind capacity from 15MW to 2 GW by 2020. The wind farm offers competitive electricity prices across a region with a healthy economy, and it currently provides enough clean energy to power the equivalent of 6,000 homes, while offsetting the production of nearly 612,000 CO2e.

Water: Climate change can jeopardize water supply and water quality in many ways, from shortages during droughts, to system stress during floods, to water pollution/contamination brought on by flooding or coastal saltwater intrusion. ASCE estimates that the investment gap in water and wastewater infrastructure in the U.S. will be more than $10.5 billion per year through 2025. We look for opportunities to invest in projects that improve efficiency of water delivery, incentivize water conservation and increase water recycling, with a focus on water-stressed regions. Resiliency of water systems will be critical for cities impacted by warming temperatures. Additionally, investments that improve stormwater management and flood protection systems can better prepare cities that will be impacted by increasingly catastrophic weather events.

Denver Water, a water utility serving 1.4 million residents, is a recent investment of ours generating positive impact. Denver relies heavily on runoff from the Rocky Mountains for its water, so it is especially vulnerable to drought caused by climate-driven precipitation changes. The Joint Front Range Climate Change Vulnerability Study estimates that even if precipitation patterns don’t change, warming of 5° F in the region could decrease water supply by 20% and increase water use by 7%. To ensure long-term water availability, Denver Water is engaged in a variety of long-term initiatives, including reservoir expansion projects, water recycling projects and conservation efforts. The utility states that the population it serves has grown by 50% since the early 1970s, but water use has increased just 6% in that timeframe.

CHALLENGES AND NEXT STEPS

We believe that cities and states are increasingly motivated to protect themselves from environmental disaster and potential damage to their credit ratings, so we are optimistic that climate-related municipal issuance will continue to grow across a variety of public sectors and that issuers and agencies will increasingly factor climate into the overall framework of municipal fiscal responsibility.

But challenges remain. Transparency and disclosure regarding climate risk are being encouraged by ratings agencies, but issuers still have reasons to drag their feet: it takes a lot of work to provide the necessary transparency, and there is little to no evidence—yet—that avoiding disclosure will impact the pricing of any newly-issued bond.

We see this as a clear opening for further engagement with issuers, regulatory authorities and other stakeholders. We currently engage with issuers individually about their climate mitigation plans, and we’ve learned that many municipalities are making notable progress on climate risk management but that their efforts are not always translated into the bond documents available to us. We are also working with CDP (formerly, the Carbon Disclosure Project) to lend an investor perspective to its ongoing work in the credit sector, and to encourage municipal issuers to disclose climate-related risks through CDP’s voluntary disclosure questionnaire for cities.

While there is still plenty of work to be done, we are enthusiastic about the growth in climate-focused municipal debt, and the more recent steps by municipalities and ratings agencies to further solidify the framework by which climate risk will be quantified and evaluated in the future.

- USGCRP, 2018: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, 1515 pp. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.

- Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact Sea Level Rise Work Group (Compact). October 2015. Unified Sea Level Rise Projection for Southeast Florida. A document prepared for the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact Steering Committee. 35 p.

The views expressed are those of Brown Advisory as of the date referenced and are subject to change at any time based on market or other conditions. These views are not intended to be and should not be relied upon as investment advice and are not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance and you may not get back the amount invested.

The information provided in this material is not intended to be and should not be considered to be a recommendation or suggestion to engage in or refrain from a particular course of action or to make or hold a particular investment or pursue a particular investment strategy, including whether or not to buy, sell, or hold any of the securities mentioned. It should not be assumed that investments in such securities have been or will be profitable. To the extent specific securities are mentioned, they have been selected by the author on an objective basis to illustrate views expressed in the commentary and do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for advisory clients. The information contained herein has been prepared from sources believed reliable but is not guaranteed by us as to its timeliness or accuracy, and is not a complete summary or statement of all available data. This piece is intended solely for our clients and prospective clients, is for informational purposes only, and is not individually tailored for or directed to any particular client or prospective client.

Any accounting, business or tax advice contained in this communication, including attachments and enclosures, is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues, nor a substitute for a formal opinion, nor is it sufficient to avoid tax-related penalties.