The traditional goal for a nonprofit’s investment portfolio was to earn a 5% return or so that could be used to fund the nonprofit’s programs. Today, we help nonprofits make an impact with the other 95% of their portfolio.

Until recently, the role of a nonprofit’s investment portfolio was straightforward: Meet a designated annual spending rate or growth rate while preserving the underlying investment capital. In other words, the portfolio was structured to use a small portion of funds each year on the nonprofit’s mission—a variable amount for endowments, and usually a required 5% minimum distribution for private foundations. The “other 95%” of the portfolio existed solely as a financial engine.

That began to change when nonprofit boards started asking a seemingly radical question: "How can we advance our mission with the other 95%?"

The concept of ethical screening in portfolios is not new—religious institutions have screened their portfolios for years. But in the past few decades, nonprofits have started looking at more comprehensive methods of driving their mission with a larger portion of their portfolio investments, and using their invested capital to generate positive impact.

From its first days as an investment firm, Brown Advisory has helped endowments and foundations tackle these mission-related investment challenges. In this article, we discuss how we help nonprofits develop and implement their mission-driven investment strategies, and we cover some of the specific structures that organizations can use to achieve financial and impact objectives at the same time.

Developing Sustainable Investment Plans

Standard Process, Added Layers of Thought

In our work with all of our endowment and foundation clients, we follow a disciplined process to ensure that we:

- Discover and fully understand the nonprofit’s long-term objectives.

- Establish or refine its investment policy in accordance with the organization’s objectives.

- Implement a diversified portfolio that conforms to the nonprofit’s investment policy, using carefully selected funds and managers within each asset class.

When a nonprofit wants a mission-aligned investment strategy, we use the same process. The only differences along the way are the additional questions and considerations we bring to bear in each step.

Discovery: This is the first and most important step in any investment strategy exercise. Far too often, nonprofits grow their capacity and budget, and even expand their core missions, but do not adapt their investment programs to serve their evolving needs. It is essential to get this discovery step right—both up front, and in periodic reviews over time—so that the portfolio truly delivers desired outcomes.

The importance of discovery is doubly important to set the stage for a mission-aligned investment program. When our clients want to include mission-driven investments in a portfolio, it adds another dimension of goals and priorities to the discovery exercise. We need to think about both financial and impact factors when discussing the client’s long-term objectives, and we need to consider a more complex equation when determining how we will measure the portfolio’s ultimate success.

Our conversations with mission-focused clients often begin with a fundamental conversation about values and priorities. Our clients rarely have difficulty expressing their primary mission, but when it comes to the details, things can get fuzzy. For example, many of our clients want to support the environment with their investments, but they differ in priorities— some are more focused on climate change, others on air pollution, still others on ensuring clean water for populations in developing countries. Also, clients differ on which issues they view as purely programmatic (i.e., best handled via grantmaking), and which issues they consider more appropriate to tackle with creative impact investments. Finally, different members of a nonprofit’s investment committee may disagree on some of these matters, and the investment committee may in turn disagree with some of the organization’s other stakeholders. A vigorous discovery process helps us dig through these questions, build consensus and compromise among key constituencies, and develop a more robust footing for subsequent planning.

Our conversations with mission-focused clients often begin with a fundamental conversation about values and priorities. Our clients rarely have difficulty expressing their primary mission, but when it comes to the details, things can get fuzzy. For example, many of our clients want to support the environment with their investments, but they differ in priorities— some are more focused on climate change, others on air pollution, still others on ensuring clean water for populations in developing countries. Also, clients differ on which issues they view as purely programmatic (i.e., best handled via grantmaking), and which issues they consider more appropriate to tackle with creative impact investments. Finally, different members of a nonprofit’s investment committee may disagree on some of these matters, and the investment committee may in turn disagree with some of the organization’s other stakeholders. A vigorous discovery process helps us dig through these questions, build consensus and compromise among key constituencies, and develop a more robust footing for subsequent planning.

Investment Policy: After this discovery process, we move into the investment policy phase, when we help codify the goals of the organization into an investment policy statement (IPS) with clear long-term objectives and specific parameters for portfolio allocation and investment selection.

We work with some of our clients to help them develop their first formal investment policy, but more often we refine or enhance a client’s existing policy to better reflect that client’s current situation. This is especially true with clients embarking on mission alignment—typically, such clients have a financially driven IPS, and we help them to layer their mission into that IPS framework.

For a mission-aligned investment strategy, we consider it important to include language in the IPS that explicitly permits the investment committee to consider impact investing and defines the types of impact investments that are appropriate for the portfolio. This specificity helps guide the nonprofit’s board and investment committee members as they carry out their fiduciary duty. Additionally, it ensures that we have clarity in our role as investment advisor, and that we have specific criteria we can use to evaluate potential investments and shape the client’s overall portfolio. Finally, it sends a clear signal to major donors about an organization’s holistic commitment to its purpose.

In addition to broad parameters regarding desired/ undesired investments, the IPS is often used to define screening rules for the portfolio. These rules may seem like they would be straightforward, but they become quite complicated at a granular level. If a nonprofit wants to screen out alcohol, does that mean zero tolerance, or is a small percentage of revenue acceptable? Does it want to focus solely on manufacturers, or extend screening to organizations that distribute alcohol, partner with alcohol companies, and so forth? We generally advise clients to provide broader guidelines in their IPS, and then we work with them to develop more refined parameters during implementation. This approach ensures clarity in the implementation phase, while still enabling the nonprofit and its advisors to have some flexibility to adapt to market developments.

Implementation: Once the IPS process is complete, we are ready to help the nonprofit implement new portfolio investments.

Regardless of whether a client is focused on mission alignment, it is very rare that the implementation process results in an immediate, wholesale reinvestment of a client’s portfolio. Portfolio transition is almost always a gradual process, in which exits from certain investments and entries into new ones are guided by our fundamental research as well as market conditions.

When adopting sustainable investment principles, it often makes sense to proceed in a gradual, incremental manner. One reason is that a gradual process helps investment committees gain familiarity over time with new criteria and new flows of information about the portfolio. It also helps with ensuring that newly adopted guidelines are producing the expected results in terms of impact, returns, dispersion and other important metrics. Finally, a gradual process is simply a way for all organizational stakeholders to gain comfort with changes in investment strategy at a controlled and comfortable pace.

A key positive development for endowments and foundations is the expanded toolkit of mission-aligned investment options available to them today. Nonprofits can still pursue “sin stock” screening, proxy voting and shareholder advocacy, while also considering a rapidly evolving range of impact investments that creatively pursue both financial and mission-related results.

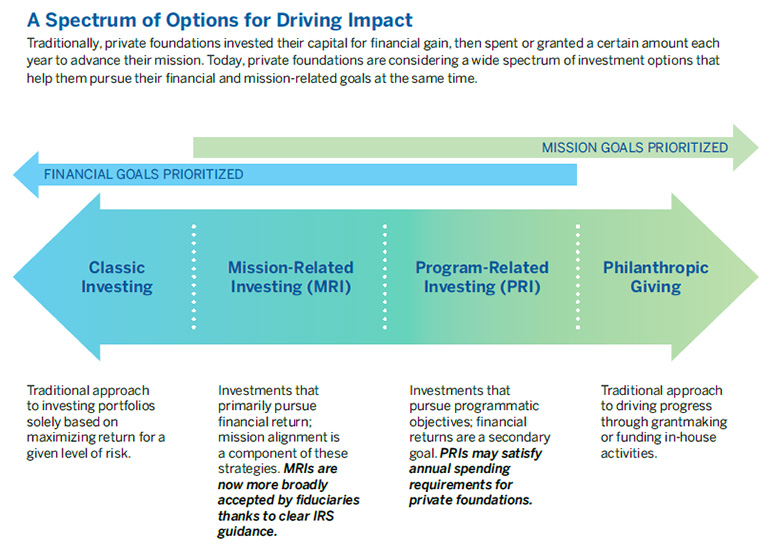

As shown in the chart below, many investors and advisors look at mission-aligned investing along a spectrum of potential outcomes, from purely financial to purely impact-focused. The traditional “5%/95%” approach to managing foundation capital would involve a series of annual grants (which would appear on the right side of the chart below), and then investment in a broad set of equity, fixed income and other assets without regard to mission-related factors (which would appear on the left side of this chart).

More and more, nonprofits want to explore ways to put that “other 95%” to work at other points on this spectrum. Microlending funds can offer loans to small businesses or farms in developing economies. Private funds can provide equity capital to startups in renewable energy or other targeted areas. Direct loans or equity investments in mission-driven businesses can generate positive outcomes for the environment or the local community. All of these sit somewhere in the middle of the impact spectrum, and offer different ways of balancing financial returns with impact generation.

Specific Options for Sustainable Investment Portfolios

Fiduciary Considerations for Program-Related and Mission-Related Investments

Many of these investments along the impact spectrum are classified as program-related investments (PRIs) and/or mission-related investments (MRIs). The legal distinctions and tax ramifications of PRIs and MRIs are mostly relevant to private foundations, but we have helped many other types of nonprofits explore these investment options as part of their overall impact strategy.

Many of these investments along the impact spectrum are classified as program-related investments (PRIs) and/or mission-related investments (MRIs). The legal distinctions and tax ramifications of PRIs and MRIs are mostly relevant to private foundations, but we have helped many other types of nonprofits explore these investment options as part of their overall impact strategy.

Briefly, a PRI’s primary objective is to further a foundation’s charitable purpose, and, in certain cases, these investments can help a private foundation satisfy its annual distribution requirements. An MRI’s primary objective is income and/or capital appreciation, but it still aligns in some way with a foundation’s mission.

In the past, the regulatory framework for permitting such investments was relatively vague, causing concern for many nonprofits and leading them to avoid impact investments that they may have otherwise wished to pursue. The good news: In recent years, the IRS has offered clear guidance to foundations about the permissibility of MRI and PRI investing, removing much of the perceived uncertainty regarding the treatment of such investments.

Program-related investments are defined by statute as an exception to the “jeopardizing investment” rules. In short, jeopardizing investment rules may impose a tax on a private foundation for any investment that might jeopardize the carrying out of its tax-exempt purposes. The Internal Revenue Code states that private foundations are able to invest in PRIs, and that such investments are not considered jeopardizing investments, so long as the investment a) has the primary objective of furthering the charitable purpose of the organization and b) does not have income or capital appreciation as a primary objective. In 2012, the IRS issued further guidance that confirmed PRI “status” for an expanded set of investments (such as investments supporting charitable activities in foreign countries, credit enhancement or guarantee arrangements) and a wider variety of charitable purposes (such as environmental programs, disaster relief, advancement of science, and other areas).

In addition to the mission-aligned progress that PRIs aim to achieve, certain PRIs offer an additional benefit: They can be considered qualifying distributions that satisfy the distribution requirements for private foundations in the year that the investment is made. A traditional qualifying distribution, like a grant, is a one-time use of capital, but a PRI may allow a nonprofit to leverage its assets more effectively. For example, a below-market-rate loan to an organization might produce similar impact to a comparable grant, and if and when repaid, the nonprofit would be able to use those assets again—plus any interest earned—to further its mission. (We should also note that if the PRI turns out to provide attractive income or capital appreciation, there is no subsequent tax penalty for the fact that it succeeded.)

Mission-related investments are different from PRIs in that they are not clearly defined by statute, but by IRS-issued guidance. Such investments are generally defined as investments that a nonprofit makes, in part, to further its programmatic aims. While this definition sounds similar to PRIs, the critical difference is that MRIs refer to investments with a primary objective of financial return.

MRIs might take the form of portfolios that are screened according to environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria. Many socially responsible mutual funds may be considered an MRI. Brown Advisory manages several sustainable equity and fixed income strategies that can be considered MRIs; these strategies explicitly use ESG data in an effort to enhance returns, and many of the holdings across these strategies are producing positive environmental impact.

MRIs, then, are a valuable tool for a foundation seeking to advance its mission in “the other 95%” of its portfolio. A growing number of “traditional” strategies in equities, fixed income and other asset classes (Brown Advisory’s included) allow endowments and foundations to align their portfolios more closely with their missions, without sacrificing performance.

Historically, many foundations were hesitant to pursue MRIs because of a lack of guidance surrounding the regulatory and tax consequences of such investments. While the IRS provided a statutory exemption from the jeopardizing investments rule for PRIs, no such exemption exists for MRIs. As a result, many fiduciaries were uncomfortable with MRIs; they reasoned that if an MRI could potentially produce reduced returns or increased dispersion from a benchmark due to consideration of ESG factors, it may be considered a jeopardizing investment.

However, the IRS provided much more concrete guidance on this topic in 2015. IRS Notice 2015-62 stated that foundations may consider a full range of factors when exercising prudence, and that nonprofits “are not required to select only investments that offer the highest rates of return, the lowest risks, or the greatest liquidity.” Further, it stated that MRIs will not be viewed as jeopardizing investments "so long as the foundation managers exercise the requisite ordinary business care and prudence" in evaluating them. Finally, it stated clearly that any potential MRI should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and once a determination is made to the contrary, it will not be judged a jeopardizing investment even if it ultimately loses money.

The upshot of all of these developments is that endowments and foundations now have a much clearer regulatory runway than ever before for launching a more expansive mission-aligned investment strategy. We try to help clients explore this expanded universe. Of course, it is still perfectly valid to view a portfolio’s capacity for impact based on its annual spend rate. Many endowments and foundations currently operate this way and will continue to do so for many years, and will no doubt fund important work that advances their organizational missions. However, if a nonprofit wishes to look at options outside of the 5% or similar amount that it spends each year on programs, there is a wide range of tools we can use to help it leverage the other 95% of its portfolio. In so doing, a nonprofit may create greater alignment with its mission, more opportunity for engagement with its key outside stakeholders and greater progress toward its programmatic goals.

The views expressed are those of the author and Brown Advisory as of the date referenced and are subject to change at any time based on market or other conditions. These views are not intended to be and should not be relied upon as investment advice and are not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance and you may not get back the amount invested.

The information provided in this material is not intended to be and should not be considered to be a recommendation or suggestion to engage in or refrain from a particular course of action or to make or hold a particular investment or pursue a particular investment strategy, including whether or not to buy, sell, or hold any of the securities or asset classes mentioned. It should not be assumed that investments in such securities or asset classes have been or will be profitable. To the extent specific securities are mentioned, they have been selected by the author on an objective basis to illustrate views expressed in the commentary and do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for advisory clients. The information contained herein has been prepared from sources believed reliable but is not guaranteed by us as to its timeliness or accuracy, and is not a complete summary or statement of all available data. This piece is intended solely for our clients and prospective clients, is for informational purposes only, and is not individually tailored for or directed to any particular client or prospective client. Private investments mentioned in this article may only be available for qualified purchasers and accredited investors. All charts, economic and market forecasts presented herein are for illustrative purposes only. Note that this data does not represent any Brown Advisory investment offerings.

Any business or tax discussion contained in this communication is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues.